ඩූ ෆූ

මෙම ලිපිය යාවත් කාලීන කිරීම අවශ්යයි. |

මෙම ලිපිය වැඩිදියුණු කළයුතුව ඇත. ඔබ මෙම මාතෘකාව පිලිබඳව දැනුවත්නම්, නව කරුණු එක්කිරීමට දායකවන්න. |

ඩූ ෆූ (චීන: 杜甫; පින්යින්: ඩූ ෆූ; වේඩ්-ගයිල්ස්: ටූ ෆූ, 712–770) යනු තාං රාජවංශය පාලනය කල සමයෙහි ජීවත්වූ ප්රසිද්ධ චීන කවියෙකි. ලි බායි (ලි පො) සහ මොහු ශ්රේෂ්ටතම චීන කවීන් ලෙස හඳුන්වයි.[1] සාර්ථක සමාජ සේවකයෙකු ලෙස තම රටට සේවය කිරීම ඔහුගේ විශිෂ්ටතම අභිලාෂය විය. නමුත් ඔහුට අවශ්ය ඉඩකඩ ලබා ගැනීමට නොහැකි විය. මුළුමහත් දේශයම මෙන් ඔහුගේ ජිවිතය ද 755 වසරේ ලූෂන් කැරැල්ල මගින් විනාශයට පැමිණියේය. එමෙන්ම ඔහුගේ දිවියේ අවසන් වසර 15 නොවෙනස් වූ අසහනයකින් යුතුව ගතකළ කාල පරිච්ඡේදයක් විය.

| ඩූ ෆූ (杜甫) | |

|---|---|

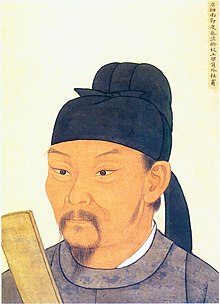

ඩූ ෆූ ගේ සමකාලීන ආලේඛ්ය චිත්ර සොයාගැනීමට නැත; මෙය පසුකාලීන චිත්රශිල්පියෙකුගේ සංකල්පිත චිත්රයකි | |

| වෘත්තිය | කවියා |

ආභාෂයට නතු කලේ | |

මුලදී අනෙකුත් ලේඛකයන්ට ආගන්තුක වුවද, චීන සහ ජපන් සාහිත්ය කෙරෙහි ඔහුගේ කාර්යයන් ඉමහත් ලෙස බලපෑම් ඇති කරන ලදී. ඔහුගේ කාව්යමය රචනයන් අතුරින් එක්දහස් පන්සියයක් පමණ දිගු කලක් තිස්සේ සුරැකී තිබුණි.[1] චීන විචාරකයන් විසින් ඔහු කිවි-ඉතිහාසඥ සහ කාව්ය-ප්රබුද්ධ ලෙස හඳුන්වනු ලැබිණි. "චීන වර්ජිල්, හොරස්, ඔවිඩ්, ශේක්ස්පියර්, මිල්ටන්, බර්න්ස්, වර්ඩ්ස්වර්ත්, බෙරේන්ජර්, හියුගෝ හෝ බවුඩෙලයර්" ලෙස බටහිර සාහිත්යයට හඳුන්වා දෙනු ලැබීමට ඔහුගේ කාර්යයන් මංපෙත් විවර කර දුනි.[2]

Life

සංස්කරණය| නම් | |

|---|---|

| චීන: | 杜甫 |

| පින්යින්: | ඩූ ෆූ |

| වේඩ්-ගයිල්ස්: | ටූ⁴ ෆූ³ |

| සී: | සීමෙයි 子美 |

| මෙලෙසද හැඳින්වේ: | ඩූ ෂැඕලිං 杜少陵 ෂැඕලිං හී ඩූ ඩූ ගොංබූ 杜工部 කර්මාන්ත අමාත්යාංශයෙහි ඩූ ෂැඕලිං යෙලාඕ 少陵野老 ෂිෂෙං, 詩圣, කවියට අධිගෘත මුනිවරයා ෂිෂි, 詩史, කාව්යමය ඉතිහාසඥයා |

Traditionally, Chinese literary criticism has placed great emphasis on knowledge of the life of the author when interpreting a work, a practice which Watson attributes to "the close links that traditional Chinese thought posits between art and morality".[3] This becomes all the more important in the case of a writer such as Du Fu, in whose poems morality and history are so prominent. Another reason, identified by the Chinese historian William Hung, is that Chinese poems are typically extremely concise, omitting circumstantial factors which may be relevant, but which could be reconstructed by an informed contemporary. For modern western readers therefore, "The less accurately we know the time, the place and the circumstances in the background, the more liable we are to imagine it incorrectly, and the result will be that we either misunderstand the poem or fail to understand it altogether".[4]

War

සංස්කරණයThe An Lushan Rebellion began in December 755, and was not completely crushed for almost eight years. It caused enormous disruption to Chinese society: the census of 754 recorded 52.9 million people, but that of 764 just 16.9 million, the remainder having been killed or displaced. During this time, Du Fu led a largely itinerant life, being kept unsettled by wars, associated famines and imperial displeasure. This period of unhappiness, however, was the making of Du Fu as a poet: Eva Shan Chou has written that, "What he saw around him– the lives of his family, neighbors, and strangers– what he heard, and what he hoped for or feared from the progress of various campaigns– these became the enduring themes of his poetry".[5] Even when he learned of the death of his youngest child, he turned to the suffering of others in his poetry instead of dwelling upon his own misfortunes.[1] Du Fu wrote:

- "Brooding on what I have lived through, if even I know such suffering, the common man must surely be rattled by the winds."[1]

In 756 Emperor Xuanzong was forced to flee the capital and abdicate. Du Fu, who had been away from the city, took his family to a place of safety and attempted to join up with the court of the new emperor (Suzong), but he was captured by the rebels and taken to Chang’an. In the autumn, his youngest son Du Zongwu (Baby Bear) was born. Around this time Du Fu is thought to have contracted malaria.

He escaped from Chang'an the following year, and was appointed Reminder when he rejoined the court in May 757. This post gave access to the emperor, but was largely ceremonial. Du Fu's conscientiousness compelled him to try to make use of it: he soon caused trouble for himself by protesting against the removal of his friend and patron Fang Guan on a petty charge; he was then himself arrested, but was pardoned in June. He was granted leave to visit his family in September, but he soon rejoined the court and on December 8, 757, he returned to Chang’an with the emperor following its recapture by government forces. However, his advice continued to be unappreciated, and in the summer of 758 he was demoted to a post as Commissioner of Education in Huazhou. The position was not to his taste: in one poem, he wrote:

- "I am about to scream madly in the office/Especially when they bring more papers to pile higher on my desk."

He moved on again in the summer of 759; this has traditionally been ascribed to famine, but Hung believes that frustration is a more likely reason. He next spent around six weeks in Qinzhou (now Tianshui, Gansu province), where he wrote over sixty poems.

Last years

සංස්කරණයLuoyang, the region of his birthplace, was recovered by government forces in the winter of 762, and in the spring of 765 Du Fu and his family sailed down the Yangtze, apparently with the intention of making their way back there. They travelled slowly, held up by his ill-health (by this time he was suffering from poor eyesight, deafness and general old age in addition to his previous ailments). They stayed in Kuizhou (now Baidicheng, Chongqing) at the entrance to the Three Gorges for almost two years from late spring 766. This period was Du Fu's last great poetic flowering, and here he wrote 400 poems in his dense, late style. In autumn 766 Bo Maolin became governor of the region: he supported Du Fu financially and employed him as his unofficial secretary.

In March 768 he began his journey again and got as far as Hunan province, where he died in Tanzhou (now Changsha) in November or December 770, in his 59th year. He was survived by his wife and two sons, who remained in the area for some years at least. His last known descendant is a grandson who requested a grave inscription for the poet from Yuan Zhen in 813.

Hung summarises his life by concluding that, "He appeared to be a filial son, an affectionate father, a generous brother, a faithful husband, a loyal friend, a dutiful official, and a patriotic subject."

Works

සංස්කරණයCriticism of Du Fu's works has focused on his strong sense of history, his moral engagement, and his technical excellence.

Notes

සංස්කරණයReferences

සංස්කරණය- Ch'en Wen-hua. T'ang Sung tzu-liao k'ao.

- Chou, Eva Shan; (1995). Reconsidering Tu Fu: Literary Greatness and Cultural Context. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44039-4.

- Cooper, Arthur (translator); (1986). Li Po and Tu Fu: Poems. Viking Press. ISBN 0-14-044272-3.

- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais, (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Hawkes, David; (1967). A Little Primer of Tu Fu. Oxford University Press. ISBN 962-7255-02-5.

- Holyoak, Keith (translator); (2007). Facing the Moon: Poems of Li Bai and Du Fu. Durham, NH: Oyster River Press. ISBN 978-1-882291-04-5.

- Hung, William; (1952). Tu Fu: China's Greatest Poet. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-7581-4322-2.

- McCraw, David; (1992). Du Fu's Laments from the South. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1422-3.

- Owen, Stephen (editor); (1997). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-97106-6.

- Rexroth, Kenneth (translator); (1971). One Hundred Poems From the Chinese. New Directions Press. ISBN 0-8112-0180-5.

- Seth, Vikram (translator); (1992). Three Chinese Poets: Translations of Poems by Wang Wei, Li Bai, and Du Fu. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-16653-9.

- Watson, Burton (editor); (1984). The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-05683-4.

- Watson, Burton (translator); (2002). The Selected Poems of Du Fu. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12829-0.

External links

සංස්කරණය- Tu Fu's poems සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 2004-08-17 at the Wayback Machine included in 300 Selected Tang poems, translated by Witter Bynner

- Du Fu: Poems A collection of Du Fu's poetry by multiple translators.

- Du Fu's poems organized roughly by date written; shows both simplified and traditional characters

- ඩූ ෆූ at the Open Directory Project