සුඩානයේ රජය සහ දේශපාලනය

උප ජනාධිපති අහමඩ් අවාඩ් ඉබන් අවුෆ්ගේ නායකත්වයෙන් යුත් හමුදා කුමන්ත්රණයකින් ජනාධිපති ඕමාර් අල් බෂීර්ගේ පාලන තන්ත්රය පෙරලා දමන 2019 අප්රේල් දක්වා සුඩානයේ දේශපාලනය විධිමත් ලෙස සිදු වූයේ ෆෙඩරල් ඒකාධිපති ඉස්ලාමීය ජනරජයක රාමුව තුළ ය. මූලික පියවරක් ලෙස ඔහු රටේ අභ්යන්තර කටයුතු කළමනාකරණය කිරීම සඳහා සංක්රාන්ති හමුදා කවුන්සිලය ස්ථාපිත කළේය. ඔහු ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාව අත්හිටුවා ද්වි-මණ්ඩල පාර්ලිමේන්තුව - ජාතික ව්යවස්ථාදායකය, එහි ජාතික සභාව (පහළ කුටිය) සහ ප්රාන්ත කවුන්සිලය (ඉහළ මණ්ඩලය) සමඟ විසුරුවා හැරියේය. කෙසේ වෙතත්, ඉබ්නු අවුෆ් එක් දිනක් පමණක් තනතුරේ රැඳී සිටි අතර පසුව ඉල්ලා අස්විය, පසුව සංක්රාන්ති හමුදා කවුන්සිලයේ නායකත්වය අබ්දෙල් ෆාටා අල්-බුර්හාන් වෙත පැවරුණි. 2019 අගෝස්තු 4 වන දින, සංක්රාන්ති හමුදා කවුන්සිලයේ නියෝජිතයින් සහ නිදහස සහ වෙනස් කිරීමේ බලවේග අතර නව ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථා ප්රකාශයක් අත්සන් කරන ලද අතර, 2019 අගෝස්තු 21 වන දින සංක්රාන්ති හමුදා කවුන්සිලය රාජ්ය නායකයා ලෙස නිල වශයෙන් 11 දෙනෙකුගෙන් යුත් ස්වෛරී කවුන්සිලයක් විසින් ප්රතිස්ථාපනය කරන ලදී, සහ සිවිල් අගමැතිවරයෙකු විසින් රජයේ ප්රධානියා ලෙස. 2023 V-Dem ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී දර්ශකවලට අනුව සුඩානය අප්රිකාවේ 6 වැනි අඩුම ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී රටයි.[1]

ෂරියා නීතිය

සංස්කරණයනිමේරි යටතේ

සංස්කරණය1983 සැප්තැම්බරයේදී, ජනාධිපති ජෆාර් නිමේරි සුඩානයේ ෂරියා නීතිය හඳුන්වා දුන් අතර එය සැප්තැම්බර් නීති ලෙස හැඳින්වේ, සංකේතාත්මකව මත්පැන් බැහැර කිරීම සහ ප්රසිද්ධියේ අත් පා කැපීම් වැනි හුඩුද් දඬුවම් ක්රියාත්මක කිරීම. අල්-තුරාබි මෙම පියවරට සහාය දැක්වීය, අල්-සාදික් අල්-මහ්දිගේ විසම්මුතික මතයට වඩා වෙනස් විය. අල්-තුරාබි සහ පාලන තන්ත්රය තුළ ඔහුගේ සහචරයින් ද දකුණේ ස්වයං පාලනයට, ලෞකික ව්යවස්ථාවකට සහ ඉස්ලාමීය නොවන සංස්කෘතික පිළිගැනීමට විරුද්ධ වූහ. ජාතික සංහිඳියාව සඳහා වූ එක් කොන්දේසියක් වූයේ, සුළුතර අයිතිවාසිකම්වලට ඉඩ සැලසීමට සහ ඉස්ලාම් ජාතිවාදය ප්රතික්ෂේප කිරීම ප්රයෝජනයට ගැනීමට අපොහොසත් වීම පිළිබිඹු කරමින්, දකුණට ස්වයං පාලනයක් ලබා දුන් 1972 අඩිස් අබාබා ගිවිසුම නැවත ඇගයීමයි.[2] ඉස්ලාමීය ආර්ථිකය 1984 මුල් භාගයේදී, පොලී ඉවත් කර සකාත් ස්ථාපිත කළේය. නිමේරි 1984 දී සුඩාන උම්මාවේ ඉමාම් ලෙස ප්රකාශ කළේය.[3]

අල් බෂීර් යටතේ

සංස්කරණයඕමාර් අල් බෂීර්ගේ පාලන සමයේදී සුඩානයේ නීති පද්ධතිය ඉස්ලාමීය ෂරියා නීතිය මත පදනම් විය. 2005 නයිවාශ ගිවිසුම, උතුරු සහ දකුණු සුඩානය අතර සිවිල් යුද්ධය අවසන් කිරීම, කාර්ටූම් හි මුස්ලිම් නොවන අය සඳහා යම් ආරක්ෂාවක් ස්ථාපිත කළේය. සුඩානයේ ෂරියා නීතිය යෙදීම භූගෝලීය වශයෙන් නොගැලපේ.[4]

ගල් ගැසීම සුඩානයේ අධිකරණ දඬුවමක් විය. 2009 සහ 2012 අතර කාන්තාවන් කිහිප දෙනෙකුට ගල් ගසා මරණ දණ්ඩනය නියම කර ඇත.[5][6][7] කස පහර දීම නීතිමය දඬුවමක් විය. 2009 සහ 2014 අතර, බොහෝ පුද්ගලයන්ට කස පහර 40-100 දක්වා දඬුවම් නියම විය.[8][9][10][11][12][13] 2014 අගෝස්තු මාසයේදී, සුඩාන ජාතිකයන් කිහිප දෙනෙකුට කස පහර දීමෙන් පසු අත්අඩංගුවේ සිටියදී මිය ගියේය.[14][15][16] 2001 දී කිතුනුවන් 53 දෙනෙකුට කස පහර දී ඇත.[17] සුඩානයේ මහජන සාමය පිළිබඳ නීතිය මගින් පොලිස් නිලධාරීන්ට ප්රසිද්ධියේ අශෝභන ලෙස හැසිරීමේ චෝදනාවට ලක් වූ කාන්තාවන්ට ප්රසිද්ධියේ කස පහර දීමට ඉඩ ලබා දී ඇත.[18]

කුරුසියේ ඇණ ගැසීම ද නීත්යානුකූල දඬුවමක් විය. 2002 දී මිනීමැරුම්, සන්නද්ධ මංකොල්ලකෑම් සහ ජනවාර්ගික ගැටුම්වලට සම්බන්ධ අපරාධ සම්බන්ධයෙන් පුද්ගලයන් 88 දෙනෙකුට මරණ දඬුවම නියම විය. ඇම්නෙස්ටි ඉන්ටර්නැෂනල් විසින් ලියා ඇත්තේ ඔවුන් එල්ලා මැරීමෙන් හෝ කුරුසියේ ඇණ ගැසීමෙන් සිදු කළ හැකි බවයි.[19]

වෙන් කිරීම් සහිතව වුවද ජාත්යන්තර අධිකරණ අධිකරණ බලය පිළිගනු ලැබේ. නයිවාෂා ගිවිසුමේ නියමයන් යටතේ, දකුණු සුඩානයේ ඉස්ලාමීය නීතිය ක්රියාත්මක නොවීය.[20] දකුණු සුඩානය වෙන්වීමත් සමඟම සුඩානයේ සිටින මුස්ලිම් නොවන සුළු ජාතීන්ට ෂරියා නීතිය ක්රියාත්මක වන්නේද යන්න පිළිබඳව යම් අවිනිශ්චිතතාවයක් ඇති විය, විශේෂයෙන්ම අල්-බෂීර් විසින් මෙම කාරණය සම්බන්ධයෙන් කරන ලද පරස්පර ප්රකාශ හේතුවෙන්.[21]

සුඩාන රජයේ අධිකරණ ශාඛාව සමන්විත වන්නේ විනිසුරන් නව දෙනෙකුගෙන් යුත් ව්යවස්ථාපිත අධිකරණයක්, ජාතික ශ්රේෂ්ඨාධිකරණය, කැසේෂන් අධිකරණය,[22] සහ අනෙකුත් ජාතික අධිකරණ; ජාතික අධිකරණ සේවා කොමිෂන් සභාව අධිකරණය සඳහා සමස්ත කළමනාකරණය සපයයි.

අල් බෂීර්ගෙන් පසු

සංස්කරණයඅල්-බෂීර් නෙරපා හැරීමෙන් පසුව, 2019 අගෝස්තු මාසයේදී අත්සන් කරන ලද අතුරු ව්යවස්ථාවේ ෂරියා නීතිය පිළිබඳ සඳහනක් නොමැත.[23] 12 ජූලි 2020 වන විට, සුඩානය ඇදහිල්ල අත්හැරීමේ නීතිය, ප්රසිද්ධියේ කස පහර දීම සහ මුස්ලිම් නොවන අය සඳහා මත්පැන් තහනම අහෝසි කළේය. නව නීතියක කෙටුම්පත ජූලි මස මුලදී සම්මත විය. සුඩානය ස්ත්රී ලිංග ඡේදනය අපරාධයක් බවට පත් කර වසර 3ක් දක්වා සිරදඬුවම් නියම කළේය.[24] සංක්රාන්ති රජය සහ කැරලිකාර කණ්ඩායම් නායකත්වය අතර ගිවිසුමක් 2020 සැප්තැම්බර් මාසයේදී අත්සන් කරන ලද අතර, ඉස්ලාමීය නීතිය යටතේ දශක තුනක පාලනය අවසන් කරමින් රාජ්යය සහ ආගම නිල වශයෙන් වෙන් කිරීමට රජය එකඟ විය. නිල රාජ්ය ආගමක් ස්ථාපිත නොකරන බවට ද එකඟ විය.[25][23][26]

පරිපාලන අංශ

සංස්කරණයසුඩානය ප්රාන්ත 18 කට බෙදා ඇත. ඒවා තවදුරටත් දිස්ත්රික්ක 133 කට බෙදා ඇත.

කලාපීය ආයතන

සංස්කරණයප්රාන්තවලට අමතරව මධ්යම රජය සහ කැරලිකාර කණ්ඩායම් අතර සාම ගිවිසුම් මගින් පිහිටුවන ලද ප්රාදේශීය පරිපාලන ආයතන ද පවතී.

- ඩාර්ෆුර් ප්රාදේශීය රජය ඩාර්ෆූර් ප්රදේශය සෑදෙන ප්රාන්ත සඳහා සම්බන්ධීකරණ ආයතනයක් ලෙස ක්රියා කිරීම සඳහා ඩාර්ෆූර් සාම ගිවිසුම මගින් පිහිටුවන ලදී.

- නැගෙනහිර සුඩාන රාජ්ය සම්බන්ධීකරණ කවුන්සිලය නැගෙනහිර ප්රාන්ත තුන සඳහා සම්බන්ධීකරණ ආයතනයක් ලෙස ක්රියා කිරීම සඳහා සුඩාන රජය සහ කැරලිකාර නැගෙනහිර පෙරමුණ අතර නැගෙනහිර සුඩාන සාම ගිවිසුම මගින් පිහිටුවන ලදී.

- දකුණු සුඩානය සහ සුඩාන ජනරජය අතර මායිමේ පිහිටා ඇති අබියි ප්රදේශය දැනට විශේෂ පරිපාලන තත්වයක් ඇති අතර එය අබියී ප්රදේශය පරිපාලනයක් මගින් පාලනය වේ. එය 2011 දී දකුණු සුඩානයේ කොටසක් ද නැතහොත් සුඩාන ජනරජයේ කොටසක් ද යන්න පිළිබඳ ජනමත විචාරණයක් පැවැත්වීමට නියමිතව තිබුණි.

මතභේදාත්මක ප්රදේශ සහ ගැටුම් කලාප

සංස්කරණය- 2012 අප්රේල් මාසයේදී දකුණු සුඩාන හමුදාව සුඩානයෙන් හෙග්ලිග් තෙල් නිධිය අල්ලා ගත් අතර පසුව එය සුඩාන හමුදාව විසින් නැවත අත්පත් කර ගන්නා ලදී.

- කාෆියා කිංගි සහ රදොම් ජාතික වනෝද්යානය 1956 දී බහර් එල් ගසල් හි කොටසක් විය.[27] 1956 ජනවාරි 1 දිනට දේශසීමා අනුව දකුණු සුඩානයේ නිදහස සුඩානය පිළිගෙන ඇත.[28]

- අබෙයි ප්රදේශය සුඩානය සහ දකුණු සුඩානය අතර මතභේදයට තුඩු දී ඇති කලාපයකි. එය දැනට සුඩාන පාලනය යටතේ පවතී.

- දකුණු කුර්දුෆාන් සහ නිල් නයිල් ප්රාන්ත සුඩානය තුළ ඔවුන්ගේ ව්යවස්ථාපිත අනාගතය තීරණය කිරීම සඳහා "ජනප්රිය උපදේශන" පැවැත්වීමට නියමිතය.

- හලායිබ් ත්රිකෝණය සුඩානය සහ ඊජිප්තුව අතර මතභේදාත්මක කලාපයකි. එය දැනට ඊජිප්තු පාලනය යටතේ පවතී.

- බීර් තාවිල් යනු කිසිදු රාජ්යයක් විසින් හිමිකම් නොකියන ඊජිප්තුව සහ සුඩානය අතර මායිමේ ඇති ටෙරා නූලියස් වර්ගයකි.

විදේශ සබඳතා

සංස්කරණය

සුඩානය එහි රැඩිකල් ඉස්ලාමීය ස්ථාවරය ලෙස සලකන දේ හේතුවෙන් එහි අසල්වැසියන් සහ බොහෝ ජාත්යන්තර ප්රජාව සමඟ කරදරකාරී සබඳතාවක් පවත්වා ඇත. 1990 දශකයේ වැඩි කාලයක් උගන්ඩාව, කෙන්යාව සහ ඉතියෝපියාව ජාතික ඉස්ලාමීය පෙරමුණු ආන්ඩුවේ බලපෑම පරීක්ෂා කිරීම සඳහා එක්සත් ජනපදයේ සහාය ඇතිව "පෙරටුගාමී රාජ්යයන්" නමින් තාවකාලික සන්ධානයක් පිහිටුවා ගත්හ. සූඩාන රජය උගන්ඩා විරෝධී කැරලිකාර කණ්ඩායම් වන ලෝඩ්ස් ප්රතිරෝධක හමුදාව (LRA) වැනි කණ්ඩායම්වලට සහාය දැක්වීය.[29]

කාර්ටූම්හි ජාතික ඉස්ලාමීය පෙරටුගාමී පාලන තන්ත්රය කලාපයට සහ ලෝකයට සැබෑ තර්ජනයක් ලෙස ක්රමක්රමයෙන් මතුවීමත් සමඟ, එක්සත් ජනපදය සුඩානය එහි ත්රස්තවාදයේ රාජ්ය අනුග්රාහක ලැයිස්තුවේ ලැයිස්තුගත කිරීමට පටන් ගත්තේය. එක්සත් ජනපදය සුඩානය ත්රස්තවාදයේ රාජ්ය අනුග්රාහකයෙකු ලෙස ලැයිස්තුගත කිරීමෙන් පසුව, NIF විසින් ඉරාකය සමඟ සබඳතා වර්ධනය කිරීමට තීරණය කළ අතර පසුව කලාපයේ වඩාත්ම මතභේදාත්මක රටවල් දෙක වන ඉරානය සමග විය.

1990 දශකයේ මැද භාගයේ සිට, 1998 එක්සත් ජනපද තානාපති කාර්යාල බෝම්බ ප්රහාර, ටැන්සානියාවේ සහ කෙන්යාවේ සහ කලින් කැරලිකරුවන්ගේ අතේ තිබූ තෙල් ක්ෂේත්රවල නව සංවර්ධනයෙන් පසුව වැඩි වූ එක්සත් ජනපද පීඩනයේ ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස සුඩානය ක්රමයෙන් එහි ස්ථාන මධ්යස්ථ කිරීමට පටන් ගත්තේය. හලායිබ් ත්රිකෝණය සම්බන්ධයෙන් සුඩානයට ඊජිප්තුව සමඟ භෞමික ආරවුලක් ද ඇත. 2003 සිට, සුඩානයේ විදේශ සබඳතා දෙවන සුඩාන සිවිල් යුද්ධය අවසන් කිරීම සඳහා සහය දැක්වීම සහ ඩාර්ෆූර්හි යුද්ධයේදී මිලීෂියාවන් සඳහා රජයේ සහයෝගය හෙළා දැකීම මත කේන්ද්රගත විය.

සුඩානය චීනය සමඟ පුළුල් ආර්ථික සබඳතා පවත්වයි. චීනය සිය තෙල්වලින් සියයට දහයක් ලබා ගන්නේ සුඩානයෙන්. සුඩාන රජයේ හිටපු ඇමතිවරයෙකුට අනුව, චීනය සුඩානයේ විශාලතම ආයුධ සැපයුම්කරු වේ.[30]

2005 දෙසැම්බරයේදී, බටහිර සහරාව මත මොරොක්කෝ ස්වෛරීභාවය පිළිගත් රාජ්ය කිහිපයෙන් එකක් බවට සුඩානය පත් විය.[31]

2015 දී, සුඩානය ෂියා හවුතිවරුන්ට එරෙහිව යේමනයේ සෞදි අරාබිය විසින් මෙහෙයවන ලද මැදිහත්වීමට සහ 2011 කැරැල්ලෙන් නෙරපා හරින ලද හිටපු ජනාධිපති අලි අබ්දුල්ලා සාලේට[32] පක්ෂපාතී හමුදාවන්ට සහභාගී විය.[33]

2019 ජූනි මාසයේදී සුඩානය අප්රිකානු සංගමයෙන් අත්හිටුවන ලද්දේ 2019 අප්රේල් 11 කුමන්ත්රණයෙන් පසුව එහි මූලික රැස්වීමේ සිට සිවිල් නායකත්වයෙන් යුත් සංක්රාන්ති අධිකාරියක් පිහිටුවීමේ ප්රගතියක් නොමැතිකම හේතුවෙනි.[34][35]

2019 ජුලි මාසයේදී, සුඩානය ඇතුළු රටවල් 37ක එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ තානාපතිවරු, ෂින්ජියැන්ග් කලාපයේ උයිගුර්වරුන්ට චීනය සලකන ආකාරය ආරක්ෂා කරමින් UNHRC වෙත ඒකාබද්ධ ලිපියක් අත්සන් කර ඇත.[36]

2020 ඔක්තෝබර් 23 දින, එක්සත් ජනපද ජනාධිපති ඩොනල්ඩ් ට්රම්ප් ප්රකාශ කළේ, සුඩානය ඊශ්රායලය සමඟ සබඳතා සාමාන්යකරණය කිරීමට පටන් ගන්නා බවත්, එක්සත් ජනපදයේ තැරැව්කාර ඒබ්රහම් ගිවිසුම්වල කොටසක් ලෙස එසේ කරන තුන්වන අරාබි රාජ්යය බවට පත් කරන බවත්ය.[37] දෙසැම්බර් 14 දින එක්සත් ජනපද රජය සුඩානය එහි රාජ්ය ත්රස්තවාදයේ අනුග්රාහක ලැයිස්තුවෙන් ඉවත් කළේය. ගිවිසුමේ කොටසක් ලෙස, 1998 තානාපති කාර්යාල බෝම්බ ප්රහාරවලින් විපතට පත් වූවන්ට වන්දි වශයෙන් ඩොලර් මිලියන 335ක් ගෙවීමට සුඩානය එකඟ විය.[38]

මහා ඉතියෝපියානු පුනරුද වේල්ල සම්බන්ධයෙන් සුඩානය සහ ඉතියෝපියාව අතර ආරවුල 2021 දී උත්සන්න විය.[39][40][41] සුඩාන නායක අබ්දෙල් ෆාටා අල්-බුර්හාන් ගේ උපදේශකයෙක් ජල යුද්ධයක් ගැන කතා කළේය "එය කෙනෙකුට සිතාගත නොහැකි තරම් බිහිසුණු වනු ඇත".[42]

2022 පෙබරවාරි මාසයේදී, රටවල් අතර සබඳතා ප්රවර්ධනය කිරීම සඳහා සුඩාන නියෝජිතයෙකු ඊශ්රායලයට ගොස් ඇති බව වාර්තා වේ.[43]

2023 මුල් මාසවලදී, මූලික වශයෙන්, හමුදා ප්රධානියා සහ තත්ය රාජ්ය නායක ජෙනරාල් අබ්දෙල් ෆටා අල්-බුර්හාන්ගේ හමුදා හමුදා සහ ඔහුගේ ප්රතිවාදියා වන ජෙනරාල් මොහොමඩ් හම්දාන් දගලෝ විසින් නායකත්වය දුන් පැරාමිලිටරි කඩිනම් සහය බලකායන් අතර, සටන් නැවත ආරම්භ විය. . එහි ප්රතිඵලයක් වශයෙන්, එක්සත් ජනපදය සහ බොහෝ යුරෝපීය රටවල් කාර්ටූම් හි පිහිටි ඔවුන්ගේ තානාපති කාර්යාල වසා දමා ඉවත් කිරීමට උත්සාහ කර ඇත. 2023 දී, සුඩානයේ සිටින ඇමරිකානුවන් 16,000 ක් ඉවත් කළ යුතු යැයි ගණන් බලා ඇත. එක්සත් ජනපද රාජ්ය දෙපාර්තමේන්තුවෙන් නිල ඉවත් කිරීමේ සැලැස්මක් නොමැති විට, බොහෝ ඇමරිකානුවන්ට මග පෙන්වීම සඳහා වෙනත් ජාතීන්ගේ තානාපති කාර්යාල වෙත හැරීමට බල කෙරී ඇත, බොහෝ දෙනෙක් නයිරෝබි වෙත පලා යති. වෙනත් අප්රිකානු රටවල් සහ මානුෂීය කණ්ඩායම් උදව් කිරීමට උත්සාහ කර ඇත. තුර්කි තානාපති කාර්යාලය ඇමරිකානුවන්ට තම පුරවැසියන් සඳහා ඉවත් කිරීමේ උත්සාහයට සම්බන්ධ වීමට අවසර දී ඇති බව වාර්තා වේ. 2017 වසරේ සිට සුඩානයේ ක්රියාත්මක වන රුසියානු පුද්ගලික හමුදා කොන්ත්රාත්කරුවෙකු වන Wagner Group සමඟ ගැටුමකට පැමිණි දකුණු අප්රිකාව පදනම් කරගත් දේශපාලන සංවිධානයක් වන TRAKboys, කළු ඇමරිකානුවන් සහ සුඩාන පුරවැසියන් දකුණු අප්රිකාවේ ආරක්ෂිත ස්ථාන කරා ඉවත් කිරීමට සහාය වෙමින් සිටී.[44][45]

2024 අප්රේල් 15 වන දින, මානුෂීය හා දේශපාලන අර්බුදයකට තුඩු දී ඇති ඊසානදිග අප්රිකානු ජාතියේ යුද්ධය පුපුරා යාමේ වසරක සංවත්සරය සනිටුහන් කරමින් ප්රංශය සුඩානය පිළිබඳ ජාත්යන්තර සමුළුවක් පවත්වයි. මැදපෙරදිග පවතින ගැටුම් හේතුවෙන් යටපත් වී ඇතැයි නිලධාරීන් විශ්වාස කරන අර්බුදයක් කෙරෙහි අවධානය යොමු කිරීමේ අරමුණින් රට ගෝලීය ප්රජාවෙන් සහාය ඉල්ලා සිටී.[46]

හමුදා

සංස්කරණයසුඩාන සන්නද්ධ හමුදාව සුඩානයේ නිත්ය හමුදාව වන අතර එය ශාඛා පහකට බෙදා ඇත: සුඩාන හමුදාව, සුඩාන නාවික හමුදාව (මැරීන් බළකාය ඇතුළුව), සුඩාන ගුවන් හමුදාව, දේශසීමා මුර සංචාර සහ අභ්යන්තර කටයුතු ආරක්ෂක බලකාය, මුළු භටයින් 200,000 ක් පමණ වේ. සුඩානයේ හමුදාව හොඳින් සන්නද්ධ සටන් බලකායක් බවට පත්ව ඇත; බර සහ දියුණු ආයුධ දේශීය නිෂ්පාදනය වැඩි කිරීමේ ප්රතිඵලයක්. මෙම බලවේග ජාතික සභාවෙහි අණ යටතේ පවතින අතර එහි මූලෝපායික මූලධර්මවලට සුඩානයේ බාහිර දේශසීමා ආරක්ෂා කිරීම සහ අභ්යන්තර ආරක්ෂාව ආරක්ෂා කිරීම ඇතුළත් වේ.

2004 ඩාර්ෆුර් අර්බුදයේ සිට, සුඩාන මහජන විමුක්ති හමුදාව (SPLA), සුඩාන විමුක්ති හමුදාව (SLA) සහ යුක්තිය සහ සමානතා ව්යාපාරය (JEM) වැනි පැරාමිලිටරි කැරලිකාර කණ්ඩායම්වල සන්නද්ධ ප්රතිරෝධයෙන් සහ කැරැල්ලෙන් මධ්යම රජය ආරක්ෂා කර ගැනීම වැදගත් ප්රමුඛතා වී ඇත. නිල නොවන නමුත්, සුඩාන හමුදාව ප්රති-කැරලිකාර යුද්ධයක් ක්රියාත්මක කිරීමේදී වඩාත් ප්රමුඛ වන්නේ ජන්ජාවීඩ් නම් නාමික මිලිෂියාවන් ද භාවිතා කරයි.[47] 200,000[48] සහ 400,000[49][50][51] අතර මිනිසුන් ප්රචණ්ඩ අරගල වලින් මිය ගොස් ඇත.

මානව හිමිකම්

සංස්කරණය1983 සිට, සිවිල් යුද්ධයේ සහ සාගතයේ එකතුවක් සුඩානයේ මිලියන දෙකකට ආසන්න මිනිසුන්ගේ ජීවිත බිලිගෙන ඇත.[52] දෙවන සුඩාන සිවිල් යුද්ධයේදී මිනිසුන් 200,000 ක් පමණ වහල්භාවයට ගෙන ඇති බවට ගණන් බලා ඇත.[53]

ක්රිස්තියානි ආගමට හැරෙන මුස්ලිම්වරුන්ට ඇදහිල්ල අත්හැරීම සඳහා මරණීය දණ්ඩනයට මුහුණ දිය හැකිය; සුඩානයේ කිතුනුවන්ට හිංසා පීඩා කිරීම සහ මාරියම් යාහියා ඊබ්රාහිම් ඉෂාග්ට (ඇත්ත වශයෙන්ම ක්රිස්තියානි ලෙස හැදී වැඩුණු) මරණ දඬුවම බලන්න. 2013 යුනිසෙෆ් වාර්තාවකට අනුව, සුඩානයේ කාන්තාවන්ගෙන් 88%ක් කාන්තා ලිංගික ඡේදනයට ලක්ව ඇත.[54] විවාහය පිළිබඳ සුඩානයේ පුද්ගලික තත්ත්ව නීතිය කාන්තා අයිතිවාසිකම් සීමා කිරීම සහ ළමා විවාහවලට ඉඩ දීම සම්බන්ධයෙන් විවේචනයට ලක්ව ඇත.[55][56] විශේෂයෙන්ම ග්රාමීය සහ අඩු අධ්යාපනයක් නොලබන කණ්ඩායම් අතර ස්ත්රී ලිංග ඡේදනය සඳහා වන සහයෝගය ඉහළ මට්ටමක පවතින බව සාක්ෂි පෙන්වා දෙයි, නමුත් මෑත වසරවලදී එය අඩුවෙමින් පවතී.[57] සමලිංගිකත්වය නීති විරෝධී ය; 2020 ජූලි වන විට එය තවදුරටත් මරණීය දණ්ඩනය වූ වරදක් නොවූ අතර ඉහළම දඬුවම ජීවිතාන්තය දක්වා සිරදඬුවමකි.[58]

2018 හි හියුමන් රයිට්ස් වොච් විසින් ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලද වාර්තාවකින් හෙළි වූයේ සුඩානය අතීත සහ වර්තමාන උල්ලංඝනයන් සම්බන්ධයෙන් වගවීම සැපයීමට අර්ථවත් උත්සාහයක් ගෙන නොමැති බවයි. ඩාර්ෆූර්, දකුණු කොර්ඩෝෆාන් සහ බ්ලූ නයිල් හි සිවිල් වැසියන්ට එරෙහි මානව හිමිකම් උල්ලංඝනය කිරීම් වාර්තාව ලේඛනගත කර ඇත. 2018 කාලය තුළ, ජාතික බුද්ධි හා ආරක්ෂක සේවය (NISS) විරෝධතා විසුරුවා හැරීම සඳහා අධික බලය භාවිතා කළ අතර ක්රියාකාරීන් සහ විපක්ෂ සාමාජිකයින් දුසිම් ගනනක් රඳවා තබා ගන්නා ලදී. එපමනක් නොව, සුඩාන හමුදා විසින් එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ-අප්රිකානු සංගමයේ හයිබ්රිඩ් මෙහෙයුම සහ අනෙකුත් ජාත්යන්තර සහන සහ ආධාර ආයතන වල අවතැන් වූ පුද්ගලයින්ට සහ ගැටුම් පවතින ප්රදේශවලට ඩාර්ෆූර් හි ප්රවේශ වීම අවහිර කරන ලදී.[59]

ඩාෆූර්

සංස්කරණය

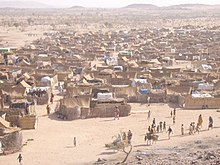

හියුමන් රයිට්ස් වොච් හි විධායක අධ්යක්ෂ විසින් 2006 අගෝස්තු 14 වැනි දින ලියූ ලිපියකින් හෙළි වූයේ සුඩාන රජයට ඩාර්ෆූර්හි සිටින තමන්ගේම පුරවැසියන් ආරක්ෂා කිරීමට නොහැකි බවත්, එසේ කිරීමට අකමැති බවත්, එහි මිලීෂියාවන් මනුෂ්යත්වයට එරෙහි අපරාධවලට වැරදිකරුවන් බවත්ය. මෙම මානව හිමිකම් උල්ලංඝනය කිරීම් 2004 වසරේ සිට පවතින බව එම ලිපියේ වැඩිදුරටත් සඳහන් වේ.[60] සමහර වාර්තාවල උල්ලංඝනය කිරීම්වලින් කොටසක් කැරලිකරුවන්ට මෙන්ම රජයට සහ ජන්ජාවීඩ් වෙත ආරෝපණය කර ඇත. 2007 මාර්තු මාසයේදී නිකුත් කරන ලද එක්සත් ජනපද රාජ්ය දෙපාර්තමේන්තුවේ මානව හිමිකම් වාර්තාව කියා සිටින්නේ," ලැව්ගින්නෙහි පාර්ශවයන් සිවිල් වැසියන් පුලුල්ව ඝාතනය කිරීම, යුද්ධයේ මෙවලමක් ලෙස ස්ත්රී දූෂණය, ක්රමානුකූල වධහිංසා පැමිණවීම, මංකොල්ලකෑම් සහ ළමා සොල්දාදුවන් බඳවා ගැනීම ඇතුළු බරපතල අපයෝජනයන් සිදු කළ බවයි."[61]

මිලියන 2.8 කට අධික සිවිල් වැසියන් අවතැන් වී ඇති අතර මියගිය සංඛ්යාව 300,000 ක් ලෙස ගණන් බලා ඇත.[62] ආන්ඩුව සමග සන්ධානගත වූ රජයේ හමුදා සහ මිලීෂියා යන දෙකම ඩාර්ෆූර්හි සිවිල් වැසියන්ට පමණක් නොව මානුෂීය සේවකයින්ට ද පහර දෙන බව දන්නා කරුණකි. විදේශ මාධ්යවේදීන්, මානව හිමිකම් ආරක්ෂකයින්, ශිෂ්ය ක්රියාකාරීන් සහ කාර්ටූම් සහ ඒ අවට අවතැන් වූවන් මෙන්, කැරලිකාර කණ්ඩායම්වලට අනුකම්පා කරන්නන් අත්තනෝමතික ලෙස රඳවා ගනු ලැබේ, ඔවුන්ගෙන් සමහරක් වධ හිංසාවලට මුහුණ දෙති. එක්සත් ජනපද රජය විසින් නිකුත් කරන ලද වාර්තාවක මානුෂීය සේවකයින්ට පහර දීම සහ අහිංසක සිවිල් වැසියන් ඝාතනය කිරීම සම්බන්ධයෙන් කැරලිකාර කණ්ඩායම්වලට ද චෝදනා එල්ල වී ඇත.[63] UNICEF ට අනුව, 2008 දී, ඩාර්ෆුර් හි ළමා සොල්දාදුවන් 6,000 ක් පමණ සිටියහ.[64]

මාධ්ය නිදහස

සංස්කරණයඕමාර් අල්-බෂීර්ගේ (1989-2019) රජය යටතේ, සුඩානයේ මාධ්ය ආයතනවලට ඔවුන්ගේ වාර්තාකරණයේ දී සුළු නිදහසක් ලබා දී ඇත.[65] 2014 දී දේශසීමා රහිත වාර්තාකරුවන්ගේ මාධ්ය ශ්රේණිගත කිරීමේ නිදහස සුඩානය රටවල් 180 න් 172 වැනි ස්ථානයට පත් කළේය.[66] 2019 දී අල්-බෂීර් නෙරපා හැරීමෙන් පසු, සිවිල් නායකත්වයෙන් යුත් සංක්රාන්ති රජයක් යටතේ කෙටි කාලයක් පැවති අතර එහිදී යම් මාධ්ය නිදහසක් තිබුණි.[65] කෙසේ වෙතත්, 2021 කුමන්ත්රණයේ නායකයින් මෙම වෙනස්කම් ඉක්මනින්ම ආපසු හැරවූහ.[67] "මෙම අංශය ගැඹුරින් ධ්රැවීකරණය වී ඇත", දේශසීමා රහිත වාර්තාකරුවෝ රට තුළ මාධ්ය නිදහස පිළිබඳ 2023 සාරාංශයේ ප්රකාශ කළහ. "මාධ්ය විචාරකයින් අත්අඩංගුවට ගෙන ඇති අතර, තොරතුරු ගලායාම වැලැක්වීම සඳහා අන්තර්ජාලය නිතිපතා වසා දමනු ලැබේ."[68] 2023 සුඩාන සිවිල් යුද්ධයේ ආරම්භයෙන් පසුව අමතර මර්දනයන් සිදු විය.[65]

සුඩානයේ ජාත්යන්තර සංවිධාන

සංස්කරණයලෝක ආහාර වැඩසටහන (WFP) වැනි එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ නියෝජිතයන් කිහිපයක් සුඩානයේ ක්රියාත්මක වේ; එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ ආහාර හා කෘෂිකර්ම සංවිධානය (FAO); එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සංවර්ධන වැඩසටහන (UNDP); එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ කාර්මික සංවර්ධන සංවිධානය (UNIDO); එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ ළමා අරමුදල (UNICEF); එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සරණාගතයින් පිළිබඳ මහ කොමසාරිස් (UNHCR); එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ පතල් සේවය (UNMAS), එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ මානුෂීය කටයුතු සම්බන්ධීකරණ කාර්යාලය (OCHA), සංක්රමණ සඳහා වූ ජාත්යන්තර සංවිධානය (IOM) සහ ලෝක බැංකුව ද පවතී.[69][70]

සුඩානය වසර ගණනාවක් පුරා සිවිල් යුද්ධයකට මුහුණ දී ඇති බැවින්, බොහෝ රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධාන (NGO) අභ්යන්තරව අවතැන් වූවන්ට උපකාර කිරීමේ මානුෂීය ප්රයත්නවල ද සම්බන්ධ වේ. රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධාන සුඩානයේ සෑම අස්සක් මුල්ලක් නෑරම, විශේෂයෙන් දකුණු කොටසේ සහ බටහිර ප්රදේශවල ක්රියාත්මක වේ. සිවිල් යුද්ධය අතරතුර, රතු කුරුස සංවිධානය වැනි ජාත්යන්තර රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධාන බොහෝ දුරට දකුණේ ක්රියාත්මක වූ නමුත් ඒවා පදනම් වී ඇත්තේ අගනුවර කාර්ටූම් හි ය.[71] ඩාර්ෆූර් ලෙස හැඳින්වෙන සුඩානයේ බටහිර ප්රදේශයේ යුද්ධය ආරම්භ වී ටික කලකට පසු රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධානවල අවධානය වෙනතකට යොමු විය. දකුණු සුඩානයේ වඩාත්ම දෘශ්යමාන සංවිධානය වන්නේ ඔපරේෂන් ලයිෆ්ලයින් සුඩාන් (OLS) සමුහයයි.[72] සමහර ජාත්යන්තර වෙළඳ සංවිධාන සුඩානය අප්රිකාවේ ග්රේටර් අං කොටසක් ලෙස වර්ගීකරණය කරයි.[73]

බොහෝ ජාත්යන්තර සංවිධාන සැලකිය යුතු ලෙස දකුණු සුඩානය සහ ඩාර්ෆූර් කලාපය යන දෙකෙහිම සංකේන්ද්රණය වී ඇතත්, ඒවායින් සමහරක් උතුරු කොටසේ ද ක්රියා කරයි. නිදසුනක් වශයෙන්, එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ කාර්මික සංවර්ධන සංවිධානය අගනුවර වන කාර්ටූම්හි සාර්ථකව ක්රියාත්මක වේ. එය ප්රධාන වශයෙන් යුරෝපීය සංගමය විසින් අරමුදල් සපයනු ලබන අතර මෑතකදී තවත් වෘත්තීය පුහුණුවක් විවෘත කරන ලදී. කැනේඩියානු ජාත්යන්තර සංවර්ධන නියෝජිතායතනය බොහෝ දුරට උතුරු සුඩානයේ ක්රියාත්මක වේ.[74]

යොමු කිරීම්

සංස්කරණය- ^ V-Dem Institute (2023). "The V-Dem Dataset". සම්ප්රවේශය 14 October 2023.

- ^ هدهود, محمود (2019-04-15). "تاريخ الحركة الإسلامية في السودان". إضاءات (අරාබි බසින්). 28 August 2023 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-08-30.

- ^ Warburg, Gabriel R. (1990). "The Sharia in Sudan: Implementation and Repercussions, 1983-1989". Middle East Journal. 44 (4): 624–637. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4328194. 2022-12-13 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-07-21.

- ^ Malik, Nesrine (6 June 2012). "Sudan's haphazard Sharia legal system has claimed too many victims". The Guardian.

- ^ Smith, David (31 May 2012). "Sudanese woman sentenced to stoning death over adultery claims". The Guardian.

- ^ "Woman faces death by stoning in Sudan".

- ^ "Rights Group Protests Stoning of Women in Sudan". November 2009.

- ^ Ross, Oakland (6 September 2009). "Woman faces 40 lashes for wearing trousers". The Toronto Star.

- ^ "Sudanese woman who married a non-Muslim sentenced to death". The Guardian. Associated Press. 15 May 2014.

- ^ "Pregnant woman sentenced to death and 100 lashes". 16 January 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 28 September 2014.

- ^ "TVCNEWS Home page". 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Detainee dies in custody in Port Sudan after court-ordered flogging – Sudan Tribune: Plural news and views on Sudan". www.sudantribune.com. 7 August 2020 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 11 April 2020.

- ^ "Sudan: Pair accused of kissing face 40 lashes". www.amnesty.org.uk.

- ^ "Detainee dies in custody in Port Sudan after court-ordered flogging". Sudan Tribune. 24 August 2014 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 21 September 2014.

- ^ "Two Sudanese men died after being detained and flogged 40 times each, says rights group". The Journal. 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Two Sudan men die after floggings: rights group". Agence France-Presse.

- ^ "Sudanese authorities flog 53 Christians on rioting charges". The BG News. 31 January 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ Kuruvilla, Carol (3 October 2013). "Shocking video: Sudanese woman flogged for getting into car with man who isn't related to her". nydailynews.com.

- ^ "Sudan: Imminent Execution/Torture/Unfair trial". Amnesty International. 17 July 2002. 3 December 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 19 December 2009.

- ^ "Field Listing – Legal System". The World Factbook. US Central Intelligence Agency. n.d. 26 December 2018 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 January 2011.

- ^ "Sharia law to be tightened if Sudan splits – president". BBC News. 19 December 2010. සම්ප්රවේශය 4 October 2011.

- ^ Michael Sheridan (23 June 2014). "Court frees Sudanese woman sentenced to death for being Christian". nydailynews.com.

- ^ a b "Sudan separates religion from state ending 30 years of Islamic rule". 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Sudan scraps apostasy law and alcohol ban for non-Muslims". BBC News. 12 July 2020. සම්ප්රවේශය 12 July 2020.

- ^ "Sudan ends 30 years of Islamic law by separating religion, state". 6 September 2020.

- ^ "Islamic world at decisive point in history: Will it take the path of Emirates or Turkey?". 6 September 2020.

- ^ "Memorial of the Government of Sudan" (PDF). The Hague: Permanent Court of Arbitration. 18 December 2008. p. xii. 15 April 2012 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ "South Sudan ready to declare independence" (Press release). Menas Associates. 8 July 2011. 29 May 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 4 June 2013.

- ^ "The world's enduring dictators ". CBS News. 16 May 2011.

- ^ Goodman, Peter S. (23 December 2004). "China Invests Heavily in Sudan's Oil Industry – Beijing Supplies Arms Used on Villagers". The Washington Post. සම්ප්රවේශය 31 May 2013.

- ^ "Sudan supports Moroccan sovereignty over Southern Provinces". Morocco Times. Casablanca. 26 December 2005. 26 February 2006 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ "U.S. Backs Saudi-Led Yemeni Bombing With Logistics, Spying". Bloomberg. 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Saudi-led coalition strikes rebels in Yemen, inflaming tensions in region". CNN. 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Sudan suspended from the African Union | African Union". au.int. සම්ප්රවේශය 30 October 2021.

- ^ "African Union suspends Sudan over coup". www.aljazeera.com (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). සම්ප්රවේශය 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Which Countries Are For or Against China's Xinjiang Policies?". The Diplomat. 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Trump Announces US-Brokered Israel-Sudan Normalization". Voice of America (VOA). 23 October 2020.

- ^ "US removes Sudan from state sponsors of terrorism list". CNN. 14 December 2020. සම්ප්රවේශය 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Sudan threatens legal action if Ethiopia dam filled without deal". Al-Jazeera. 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Egypt, Sudan conclude war games amid Ethiopia's dam dispute". Associated Press. 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Egypt and Sudan urge Ethiopia to negotiate seriously over giant dam". Reuters. 9 June 2021.

- ^ "Gerd: Sudan talks tough with Ethiopia over River Nile dam". BBC News. 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Sudanese envoy in Israel to promote ties – source". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com (ඇමෙරිකානු ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 9 February 2022. සම්ප්රවේශය 9 February 2022.

- ^ "Americans and other foreigners struggle to flee Sudan amid fierce fighting". Washington Post (ඇමෙරිකානු ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). ISSN 0190-8286. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-05-03.

- ^ "Trakboys David Mbatha, Blose begin peaceful talks w/ Mayor Kaunda about Durban Port tariff increase". YouTube. 25 July 2022.

- ^ "France hosts conference on aid to war-torn Sudan". Le Monde.fr (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 2024-04-15. සම්ප්රවේශය 2024-04-16.

- ^ "Sudan: National Security". Mongabay. n.d. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 January 2011.

- ^ "Q&A: Sudan's Darfur Conflict". BBC News. 23 February 2010. සම්ප්රවේශය 13 January 2011.

- ^ "Sudan". The World Factbook. U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. ISSN 1553-8133. සම්ප්රවේශය 10 July 2011.

- ^ "Darfur Peace Talks To Resume in Abuja on Tuesday: AU". People's Daily. Beijing. Xinhua News Agency. 28 November 2005. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 January 2011.

- ^ "Hundreds Killed in Attacks in Eastern Chad – U.N. Agency Says Sudanese Militia Destroyed Villages". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 11 April 2007. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 January 2011.

- ^ U.S. Committee for Refugees (April 2001). "Sudan: Nearly 2 Million Dead as a Result of the World's Longest Running Civil War". 10 December 2004 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 10 December 2004.

- ^ "CSI highlights 'slavery and manifestations of racism'". The New Humanitarian. 7 September 2001.

- ^ UNICEF 2013 සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 5 අප්රේල් 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 27.

- ^ "Time to Let Sudan's Girls Be Girls, Not Brides". Inter Press Service. 10 July 2013. සම්ප්රවේශය 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Sudan worst in Africa with legal marriage at age 10". Thomson Reuters Foundation. 15 February 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 15 February 2015.

- ^ Hamilton, Alexander; Kandala, Ngianga-Bakwin (February 2016). "Geography and correlates of attitude toward Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in Sudan: What can we learn from successive Sudan opinion poll data?". Spatial and Spatio-temporal Epidemiology. 16: 59–76. doi:10.1016/j.sste.2015.12.001. PMID 26919756.

- ^ "Sudan drops death penalty for homosexuality". Erasing 76 Crimes. 16 July 2020. සම්ප්රවේශය 16 July 2020.

- ^ "Sudan: Events of 2018". World Report 2019: Rights Trends in Sudan. 17 January 2019. සම්ප්රවේශය 10 July 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Letter to the U.N. Security Council on Sudan Sanctions and Civilian Protection in Darfur". Human Rights Watch. 15 August 2006. 15 October 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 4 June 2013.

- ^ "Darfur Tops U.S. List of Worst Human Rights Abuses". USA Today. Washington DC. Associated Press. 6 March 2007. සම්ප්රවේශය 8 January 2011.

- ^ "Q&A: Sudan's Darfur conflict". BBC News. 8 February 2010.

- ^ "Sudan – Report 2006". Amnesty International. 3 November 2006 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ "Africa – Sudan 'has 6,000 child soldiers'". සම්ප්රවේශය 15 February 2015.

- ^ a b c Obaji Jr, Philip (2022-06-07). "The silencing of Sudan's journalists - again" (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). Al Jazeera Media Institute. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-11-08.

- ^ Reporters Without Borders (23 May 2014). "Sudanese Authorities Urged Not to Introduce "Censorship Bureau"". allAfrica.com (Press release). සම්ප්රවේශය 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Press freedom under siege after military coup in Sudan" (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). Reporters Without Borders. 2021-05-11. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-11-08.

- ^ "Sudan". rsf.org (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). Reporters Without Borders. 2023-10-30. 2023-10-24 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-11-08.

- ^ "Sudan". International Organisation for Migration. 2 May 2013. 10 March 2012 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 31 May 2013.

- ^ "The Sudans". Gatineau, Quebec: Canadian International Development Agency. 29 January 2013. 28 May 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 31 May 2013.

- ^ "Darfur – overview". Unicef. n.d. 18 May 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 31 May 2013.

- ^ "South Sudan, Nuba Mountains, May 2003 – WFP delivered food aid via road convoy". World Food Programme. 8 May 2003. 10 August 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 31 May 2013.

- ^ Maxwell, Daniel, and Ben Watkins. "Humanitarian information systems and emergencies in the Greater Horn of Africa: logical components and logical linkages." Disasters 27.1 (2003): 72–90.

- ^ "EU, UNIDO set up Centre in Sudan to develop industrial skills, entrepreneurship for job creation" (Press release). UN Industrial Development Organisation. 8 February 2011. 15 June 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 4 June 2013.