ලෙඩ් නයිට්ට්රේට්

ලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් යනු රසායනික සූත්රය Pb(NO3)2 වූ අකාබනික සංයෝගයකි. එය සාමාන්යයෙන් වර්ණයක් රහිත ස්පටිකයක් හෝ සුදු පැහැ කුඩක් ලෙස පවතින අතර අනෙක් බොහෝ ලෙඩ්(II) ලවණ මෙන් නොව, ජලයේ හොඳින් දිය වේ.

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Lead(II) nitrate

| |||

| වෙනත් නාම

Lead nitrate

Plumbous nitrate Lead dinitrate Plumb dulcis | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| CAS number | {{{value}}} | ||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:{{{value}}} | ||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.210 | ||

| KEGG | {{{value}}} | ||

| PubChem | {{{value}}} | ||

| RTECS number | {{{value}}} | ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1469 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| InChI | |||

| SMILES | |||

| Properties | |||

| Molecular formula | Pb(NO3)2 | ||

| අණුක ස්කන්ධය | 331.2 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | White colourless crystals | ||

| Density | 4.53 g/cm3 (20 °C) | ||

| Melting point |

270 °C, decomp. | ||

| Solubility in water | 52 g/100 mL (20 °C) 127 g/100 mL (100 °C) | ||

| Solubility in nitric acid in ethanol in methanol |

insoluble 0.04 g/100 mL 1.3 g/100 mL | ||

| Solubility product, Ksp | 1.782[1] | ||

| Structure | |||

| Crystal structure | Face-centred cubic | ||

| Coordination geometry |

cuboctahedral | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Flash point | {{{value}}} | ||

| Related compounds | |||

| Other anions | Lead(II) sulfate Lead(II) chloride Lead(II) bromide | ||

| Other cations | Tin(II) nitrate | ||

| Related compounds | Thallium(III) nitrate Bismuth(III) nitrate | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

මධ්යම යුගයේ සිට plumb dulcis ලෙස හඳුන්වන මෙය ලෝහක ලෙඩ්(II) හෝ නයිට්රික් ඇසිඩ් තුළ ලෙඩ් ඔක්සයිඩ් මඟින් ලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් උත්පාදනය කුඩා ප්රමාණ වලින් සිදු වන අතර වෙනත් ලෙඩ් සංයෝග සඳහා කෙලින් ම යොදා ගැනේ. 19 වන සියවසේ දී එක්සත් ජනපදයේ සහ යුරෝපයේ ලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් වාණිජ වශයෙන් නිෂ්පාදනය ඇරඹුණි. ඓතිහාසික වශයෙන් වර්ණක නිෂ්පාදනයේ දී තීන්ත සඳහා අමු ද්රව්ය ලෙස යොදා ගැනීම ප්රධාන භාවිතය වූ නමුත් ටයිටේනියම් ඩයොක්සයිඩ් වලින් සාදන විෂ අඩු තීන්ත නිසා අභාවයට පැමිණෙමින් තිබේ. අනෙකුත් කාර්මික භාවිත වනුයේ නයිලෝන් සහ පොලියෙස්ටර වල තාප ස්ථායිකරණය සහ ඡායා තාප ලේඛ කඩදාසි වල ආලේපන යි. වසර 2000 පමණ සිට ලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් රත්රන් සයනයිඩ සඳහා යොදා ගැණින.

ලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් විෂ සහිත ඔක්සිකාරකයක් වන අතර බොහෝ විට මනුෂ්ය ශරීරයට පිළිකා කාරකයක් ලෙස පිළිකා පර්යේෂණ සඳහා වූ අන්තර්ජාතික ඒජන්සිය(International Agency for Research on Cancer) විසින් වර්ගීකරණය කොට ඇත. එම නිසා එය ආශ්වාසයෙන්, අධිග්රහණයෙන් සහ ස්පර්ශයෙන් වැළකෙන පරිදි සුදුසු ආරක්ෂිත ස්ථාන වල හැසිරවීම සහ ගබඩා කිරීම කළ යුතු වේ. ලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් වල උපද්රව සහිත ස්වාභාවය නිසා එහි සීමාසහිත භාවිත නිරන්තර සමීක්ෂණ යටතේ පවතී.

ඉතිහාසය

සංස්කරණයමධ්යම යුගයේ සිට ක්රෝමියම් කහ(lead(II) chromate), ක්රෝමියම් තැඹිලි(lead(II) hydroxide chromate), සහ සමාන ලෙඩ් සංයෝග වැනි ලෙඩ් සායම් වල දී වර්ණක සඳහා අමුද්රව්යයක් ලෙස ලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් නිෂ්පාදනය කරනු ලැබීය. මෙම වර්ණක, සායම් පෙවීම සහ කපු රෙදි වල මුද්රණය කිරීම සහ අනෙකුත් රෙදිපිළි සඳහා යොදා ගන්නා ලදී.[2]

1597 දී ජර්මානු විද්යාඥ Andreas Libavius විසින් පළමුවෙන් ම නිෂ්පාදිත plumb dulcis සහ calx plumb dulcis සංයෝග වල මධ්යකාලීන නම් වල තේරුම එහි රසය නිසා "sweet lead" යැයි නම් කළේය.[3] මතු සියවස් තුළ දී නිසියාකාර අවබෝධයක් නැති නමුත් ලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් හි පිපිරීමේ ගුණය lead azide වැනි විශේෂ ස්පෝටක සඳහා භාවිතා විය.[4]

නිෂ්පාදන ක්රියාවලිය සරල රසායනික වන අතර ජලීය නයිට්රික් ඇසිඩ් තුළ ලෙඩ් ඵලදායී ලෙස දිය වන අතර පසුව ප්රතිඵල ලෙස අවක්ෂේප ඇති කරයි. කෙසේ නමුත් නිෂ්පාදිතයෙන් කුඩා ප්රමාණයක් සියවස් ගණනාවක් ඉතිරි වූ අතර ලෙඩ් සංයෝග සෑදීමේ අමු ද්රව්යක් ලෙස ලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් හි ව්යාපාරික නිෂ්පාදනය 1835 තෙක් වාර්තා නොවීය.[5][6] 1974 දී වර්ණක සහ ගැසලීන් වැනි සංකලන ද්රව්ය හැර එක්සත් ජනපදයේ ලෙඩ් සංයෝග වල පරිභෝජනය ටොන් 642ක් විය.[7]

ව්යුහය

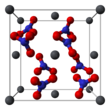

සංස්කරණයThe crystal structure of solid lead(II) nitrate has been determined by neutron diffraction.[8][9] The compound crystallises in the cubic system with the lead atoms in a face-centred cubic system. Its space group is Pa3Z=4 (Bravais lattice notation), with each side of the cube with length 784 picometres.

The black dots represent the lead atoms, the white dots the nitrate groups 27 picometres above the plane of the lead atoms, and the blue dots the nitrate groups the same distance below this plane. In this configuration, every lead atom is bonded to twelve oxygen atoms (bond length: 281 pm). All N–O bond lengths are identical, at 127 picometres.

Research interest in the crystal structure of lead(II) nitrate was partly based on the possibility of free internal rotation of the nitrate groups within the crystal lattice at elevated temperatures, but this did not materialise.[9]

සම්මිශ්රණය සහ උත්පාදනය

සංස්කරණයලෙඩ්(II) නයිට්රේට් ස්වභාවිකව නොපවතියි. ලෝහමය ලෙඩ් ජලීය නයිට්රික් අම්ලයෙහි දියකිරීමෙන් සංයෝගය සාදා ගත හැක:[7][10]

- 3 Pb (s) + 8 H+ (aq) + 2 NO-3 (aq) → 3 Pb2+ (aq) + 2 NO (g) + 4 H2O (l)

More commonly, lead(II) nitrate is obtained by dissolving lead(II) oxide, which is readily available as an intermediate in the processing of galena, in aqueous nitric acid:[7]

- PbO (s) + 2 H+ (aq) → Pb2+ (aq) + H2O (l)

In either case, since the solvent is concentrated nitric acid (in which lead(II) nitrate has very low solubility) and the resulting solution contains nitrate ions, anhydrous crystals of lead(II) nitrate spontaneously form as a result of the common ion effect:[10]

- Pb2+ (aq) + 2 NO-3 (aq) → Pb(NO3)2 (s)

Most commercially available lead(II) nitrate, as well as laboratory-scale material, is produced accordingly.[11] Supply is in 25 kilogram bags up to 1000 kilogram big bags, and in laboratory containers, both by general producers of laboratory chemicals and by producers of lead and lead compounds. No large-scale production has been reported.

In nitric acid treatment of lead-containing wastes, e.g., in the processing of lead–bismuth wastes from lead refineries, impure solutions of lead(II) nitrate are formed as by-product. These solutions are reported to be used in the gold cyanidation process.[12]

ප්රතික්රියා

සංස්කරණයApart from lead(II) acetate, lead(II) nitrate is the only common soluble lead compound. Lead(II) nitrate readily dissolves in water to give a clear, colourless solution.[13] As an ionic substance, the dissolution of lead(II) nitrate involves dissociation into its constituent ions.

- Pb(NO3)2 (s) → Pb2+ (aq) + 2 NO-3 (aq)

Lead(II) nitrate forms a slightly acidic solution, with a pH of 3.0 to 4.0 for a 20% aqueous solution.[14]

When concentrated sodium hydroxide solution is added to lead(II) nitrate solution, basic nitrates are formed, even well past the equivalence point. Up through the half equivalence point, Pb(NO3)2·Pb(OH)2 predominates, then after this point Pb(NO3)2·5Pb(OH)2 is formed. No simple Pb(OH)2 is formed up to at least pH 12.[10][15]

සංකීර්ණ බව

සංස්කරණයLead(II) nitrate is associated with interesting supramolecular chemistry because of its coordination to nitrogen and oxygen electron-donating compounds. The interest is largely academic, but with several potential applications. For example, combining lead nitrate and pentaethylene glycol (EO5) in a solution of acetonitrile and methanol followed by slow evaporation produces a new crystalline material [Pb(NO3)2(EO5)].[16] In the crystal structure for this compound, the EO5 chain is wrapped around the lead ion in an equatorial plane similar to that of a crown ether. The two bidentate nitrate ligands are in trans configuration. The total coordination number is 10, with the lead ion in a bicapped square antiprism molecular geometry.

The complex formed by lead(II) nitrate, lead(II) perchlorate and a bithiazole bidentate N-donor ligand is binuclear, with a nitrate group bridging the lead atoms with coordination number of 5 and 6.[17] One interesting aspect of this type of complexes is the presence of a physical gap in the coordination sphere; i.e., the ligands are not placed symmetrically around the metal ion. This is potentially due to a lead lone pair of electrons, also found in lead complexes with an imidazole ligand.[18]

This type of chemistry is not unique to the nitrate salt; other lead(II) compounds such as lead(II) bromide also form complexes, but the nitrate is frequently used because of its solubility properties and its bidentate nature.

ඔක්සිකරණය සහ පිපිරීම

සංස්කරණයLead(II) nitrate is an oxidising agent. Depending on the reaction, this may be due to the Pb2+(aq) ion, which has a standard reduction potential (E0) of −0.125 V, or the nitrate ion, which under acidic conditions has an E0 of +0.956 V.[19] The nitrate would function at high temperatures or in an acidic condition, while the lead(II) works best in a neutral aqueous solution.

When heated, lead(II) nitrate crystals decompose to lead(II) oxide, dioxygen and nitrogen dioxide, accompanied by a crackling noise. This effect is referred to as decrepitation.

- 2 Pb(NO3)2 (s) → 2 PbO (s) + 4 NO2 (g) + O2 (g)

Because of this property, lead nitrate is sometimes used in pyrotechnics such as fireworks.[4]

භාවිත

සංස්කරණයDue to the hazardous nature of lead(II) nitrate, there is a preference for using alternatives in industrial applications. In the formerly major application of lead paints, it has largely been replaced by titanium dioxide.[20] Other historical applications of lead(II) nitrate, such as in matches and fireworks, have declined or ceased as well. Current applications of lead(II) nitrate include use as a heat stabiliser in nylon and polyesters, as a coating for photothermographic paper, and in rodenticides.[7]

On a laboratory scale, lead(II) nitrate provides one of two convenient and reliable sources of dinitrogen tetroxide. By carefully drying lead(II) nitrate and then heating it in a steel vessel, nitrogen dioxide is produced along with dioxygen following the decripitation equation shown above. Alternatively, nitrogen dioxide is formed when concentrated nitric acid is added to copper turnings; in this case, substantial nitric oxide can also be produced. In either case, the resulting nitrogen dioxide exists in equilibrium with its dimer, dinitrogen tetroxide:

- 2 NO2 ⇌ N2O4

In order to remove either impurity, the gas mixture is condensed and fractionally distilled to give a mixture of NO2 and N2O4.[7] As the dimerisation is exothermic, low temperatures favour N2O4 as the dominant form.

To improve the leaching process in the gold cyanidation, lead(II) nitrate solution is added. Although a bulk process, only limited amounts (10 to 100 milligrams lead(II) nitrate per kilogram gold) are required.[21][22] Both the cyanidation itself, as well as the use of lead compounds in the process, are deemed controversial due to the compounds' toxic nature.

In organic chemistry, lead(II) nitrate has been used as an oxidant, for example as an alternative to the Sommelet reaction for oxidation of benzylic halides to aldehydes.[23] It has also found use in the preparation of isothiocyanates from dithiocarbamates.[24] Because of its toxicity it has largely fallen out of favour, but it still finds occasional use, for example as a bromide scavenger during SN1 substitution.[25]

සුරක්ෂිතභාවය

සංස්කරණයLead(II) nitrate is toxic, and ingestion may lead to acute lead poisoning, as is applicable for all soluble lead compounds.[26] All inorganic lead compounds are classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as probably carcinogenic to humans (Category 2A).[27] They have been linked to renal cancer and glioma in experimental animals and to renal cancer, brain cancer and lung cancer in humans, although studies of workers exposed to lead are often complicated by concurrent exposure to arsenic.[28] Lead is known to substitute for zinc in a number of enzymes, including δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (porphobilinogen synthase) in the haem biosynthetic pathway and pyrimidine-5′-nucleotidase, important for the correct metabolism of DNA and can therefore cause fetal damage.[29]

මේවාත් බලන්න

සංස්කරණය- Pigments containing lead, such as White lead, Naples Yellow, and Red lead

- Historical compounds, such as Muriatic acid, Vitriol, sugar of lead, and Sal mirabilis

යොමුව

සංස්කරණය- ^ Patnaik, Pradyot (2003). Handbook of Inorganic Chemical Compounds. McGraw-Hill. p. 475. ISBN 0-07-049439-8. සම්ප්රවේශය 2009-06-06.

- ^ Partington, James Riddick (1950). A Text-book of Inorganic Chemistry. MacMillan. p. 838.

- ^ Libavius, Andreas (1595). Alchemia Andreæ Libavii. Francofurti: Iohannes Saurius.

- ^ a b Barkley, J.B. (October 1978). "Lead nitrate as an oxidizer in blackpowder". Pyrotechnica. IV. Post Falls, ID: Pyrotechnica Publications: 16–18.

- ^ "Lead". Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition. සම්ප්රවේශය 2006-10-11.

- ^ Macgregor, John (1847). Progress of America to year 1846. London: Whittaker & Co. ISBN 0-665-51791-2.

- ^ a b c d e Greenwood, Norman N. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 388, 456. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hamilton, W.C. (1957). "A neutron crystallographic study of lead nitrate". Acta Cryst. 10 (2): 103–107. doi:10.1107/S0365110X57000304.

- ^ a b Nowotny, H. (1986). "Structure refinement of lead nitrate". Acta Cryst. C42 (2): 133–35. doi:10.1107/S0108270186097032.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Othmer, D.F. (1967). Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Vol. 12 (Iron to Manganese) (second completely revised ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 272. ISBN 0-471-02040-0.

- ^ Adlam, George Henry Joseph (1938). A Higher School Certificate Inorganic Chemistry. London: John Murray.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Product catalog; other products". Tilly, Belgium: Sidech. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-05.

- ^ Ferris, L.M. (1959). "Lead nitrate—Nitric acid—Water system". Journal of Chemicals and Engineering Date. 5 (3): 242–242. doi:10.1021/je60007a002.

- ^ http://www.mallbaker.com/americas/msds/english/L3130_msds_us_Default.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pauley, J. L. (1954). "Basic Salts of Lead Nitrate Formed in Aqueous Media". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 76 (16): 4220–4222. doi:10.1021/ja01645a062.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rogers, Robin D. (1996). "Structural Chemistry of Poly (ethylene glycol). Complexes of Lead(II) Nitrate and Lead(II) Bromide". Inorg. Chem. 35 (24): 6964–6973. doi:10.1021/ic960587b. PMID 11666874.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ Mahjoub, Ali Reza (2001). "A Dimeric Mixed-Anions Lead(II) Complex: Synthesis and Structural Characterization of [Pb2(BTZ)4(NO3)(H2O)](ClO4)3 {BTZ = 4,4'-Bithiazole}". Chemistry Letters. 30 (12): 1234. doi:10.1246/cl.2001.1234.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wan, Shuang-Yi (2002). "2D 4.8² Network with threefold parallel interpenetration from nanometre-sized tripodal ligand and lead(II) nitrate". Chem. Commun. (21): 2520–2521. doi:10.1039/b207568g.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hill, John W. (1999). General Chemistry (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 781. ISBN 0-13-010318-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Historical development of titanium dioxide". Millennium Inorganic Chemicals. October 21, 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-04.

- ^ Habashi, Fathi (1998 (est)). Recent advances in gold metallurgy. Quebec City, Canada: Laval University. 2008-03-30 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-05.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Auxiliary agents in gold cyanidation". Gold Prospecting and Gold Mining. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-05.

- ^ Schulze, K. E. (1884). "Über α- und β-Methylnaphtalin". Chemische Berichte. 17: 1530. doi:10.1002/cber.188401701384.

- ^ සැකිල්ල:OrgSynth

- ^ සැකිල්ල:OrgSynth

- ^ "Lead nitrate, Chemical Safety Card 1000". International Labour Organization, International Occupational Safety and Health Information Centre. 1999. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Inorganic and Organic Lead Compounds" (PDF). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Suppl. 7. International Agency for Research on Cancer: 239. 1987. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-19.

- ^ World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2006). "Inorganic and Organic Lead Compounds" (PDF). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 87. International Agency for Research on Cancer. ISBN 92-832-1287-8. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-01.

- ^ Mohammed-Brahim, B. (1985). "Erythrocyte pyrimidine 5'-nucleotidase activity in workers exposed to lead, mercury or cadmium". Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 55 (3): 247–52. doi:10.1007/BF00383757. PMID 2987134.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

බාහිර ඇමුණුම්

සංස්කරණය- Woodbury, William D. (1982). "Lead". Mineral yearbook metals and minerals. Bureau of Mines: 515–42. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-18.

- "Lead". NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 2005. NIOSH 2005-149. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Lead and Lead Compounds Fact Sheet". National Pollutant Inventory. Australian Government, Department of the Environment and Water Resources. 2007. January 11, 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Lead". A Healthy home environment, Health hazards. US Alliance for healthy homes. සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-19.

- "Demonstration movie: Bright Orange Yellow How can you get it". සම්ප්රවේශය 2008-01-19.

- Material Safety Data Sheets

- MSDS for lead nitrate, PTCL, Oxford University සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 2007-09-16 at the Wayback Machine

- MSDS for lead nitrate, ProSciTechPDF (126 KiB)

- MSDS for lead nitrate, Science Stuff Inc සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 2006-03-28 at the Wayback Machine

- MSDS for lead nitrate, Iowa State University සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 2006-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- MSDS for lead nitrate, NIST